The finance industry has faced many paradigm shifts in recent years. Many of these changes to the traditional way of doing things are triggered by developments in technology that were not previously available. Some are triggered by political changes and shifts in behaviour; for example, most of the tide of regulation that has occurred in the last ten years has been the result of perceived weaknesses that allowed the financial crisis of 2008 to occur. We are now poised for the next shift armed with the will, the developed (but not implemented) operational model and the technology to transform our current complex, fragmented and manual tax processing landscape into a more integrated platform-based model.

Paradigm Shift vs Evolution vs Revolution

An evolutionary shift is one that takes place over extended time and in which superior process elements are self-selecting. A revolutionary shift is one that takes place very quickly – not necessarily with the consent of those involved (e.g. via a regulator) – and where the change is not necessarily self-selecting and may therefore actually be seen as a retrograde step in hindsight. A paradigm shift represents a holistic change in the way that withholding tax is viewed. For example, ‘Tax is a product not a Task’ is an expression of a paradigm shift that changes the whole way we look at tax – from an administrative task, to a product. As a result of this shift, even though the elements of the underlying processes remain the same, the way they are treated, viewed or interpreted changes fundamentally. They change from one in which the task is an end in itself, to one in which the task is part of a service offering with a price, cost, profit model etc. The relationship between these three types of systemic change often depends on which of three factors is present: the technology, the driver for change and/or the desire or willingness to change.

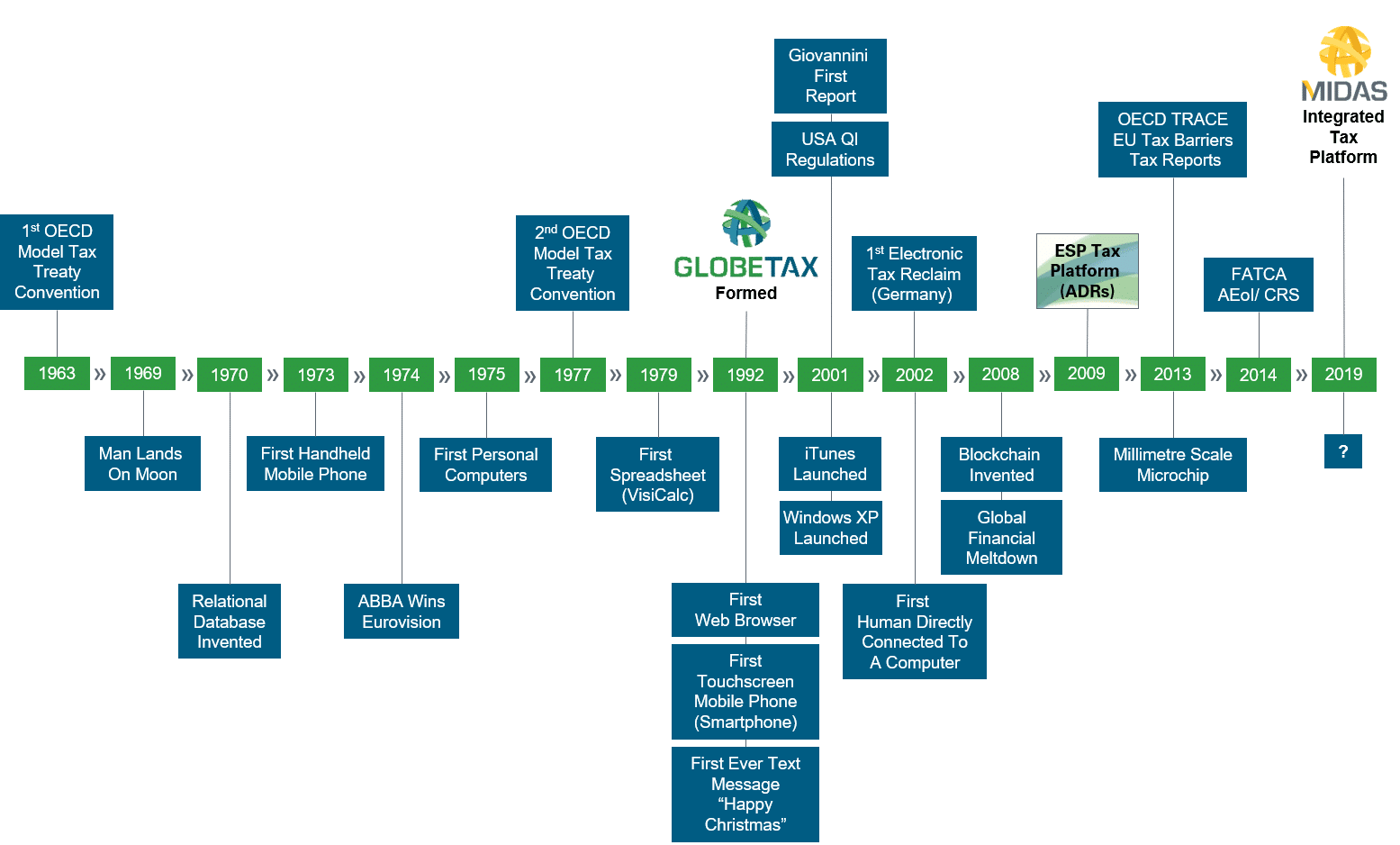

Unlike the payments or data sectors, change has been glacially slow in the world of cross border taxation, even though technologies at large have developed at a faster and faster pace. In the time between when the first and second OECD Model Tax Conventions were issued: we landed on the moon; relational databases, mobile phones and computers were invented; and ABBA won the Eurovision song contest! While the EU and OECD were thinking through their tax problems a decade after Germany launched the first ever electronic tax reclaim process (a spreadsheet), iTunes and Windows XP were launched, we connected a human being directly to a computer, blockchain was invented, the industry imploded on itself and we invented a microchip less than a millimetre across. The takeaway here is that the rate of change in general technological advances is increasing at a much faster pace than it is in the tax industry. ABBA have even managed to produce a musical and two movies since they came on the scene and they don’t even exist as a group anymore.

Figure 1 Rates of Change in Tax

The Bad Old Days

At present, and for the last few decades, withholding tax has been a very fragmented landscape in a number of different ways. Governments structured their tax treaties bilaterally, albeit often under the general model of the OECD Model Tax Convention – with the notable exception of the USA. These treaties have subsequently been ‘interpreted’ into highly complex matrices of eligibility criteria. The drivers for these complex rules were mainly concerns over tax avoidance, tax evasion, treaty abuse, treaty shopping and outright fraud.

Fragmentation – The Root of the Problem

The most predominant operating model has historically been a standard refund (or ‘long form’) model where most tax authorities interpreted domestic law and governmental edict to tax foreign investors at a high statutory rate and keep the tax until the beneficial owner came to collect it. Some authorities even claimed that the unclaimed tax was an overall benefit of that model, despite evidence that the standard refund model disproportionately damages foreign direct investment. The inefficiencies of this model were further exacerbated by the financial services community who, for different commercial reasons, often structured the custody chain of asset management using omnibus accounts.

So, even where a tax authority allowed a more efficient tax relief model, there was often insufficient transparency through to the eligible beneficial owner to allow for that tax relief to be granted at source. This is not to say that the landscape was homogeneously inefficient. Its fragmented nature allows for some markets to be more efficient than others. However, it’s the fragmentation that creates the primary problem for the industry.

The Network Effect

The secondary problems are the costly, bifurcated, manual and semi-automated processes that custodians had to have just to be able to handle the simple cases. Anything remotely complex in terms of beneficial ownership, asset servicing structures, transparency requirements or form filling just didn’t get attempted. What’s worse is that the financial world is complex in at least two dimensions.

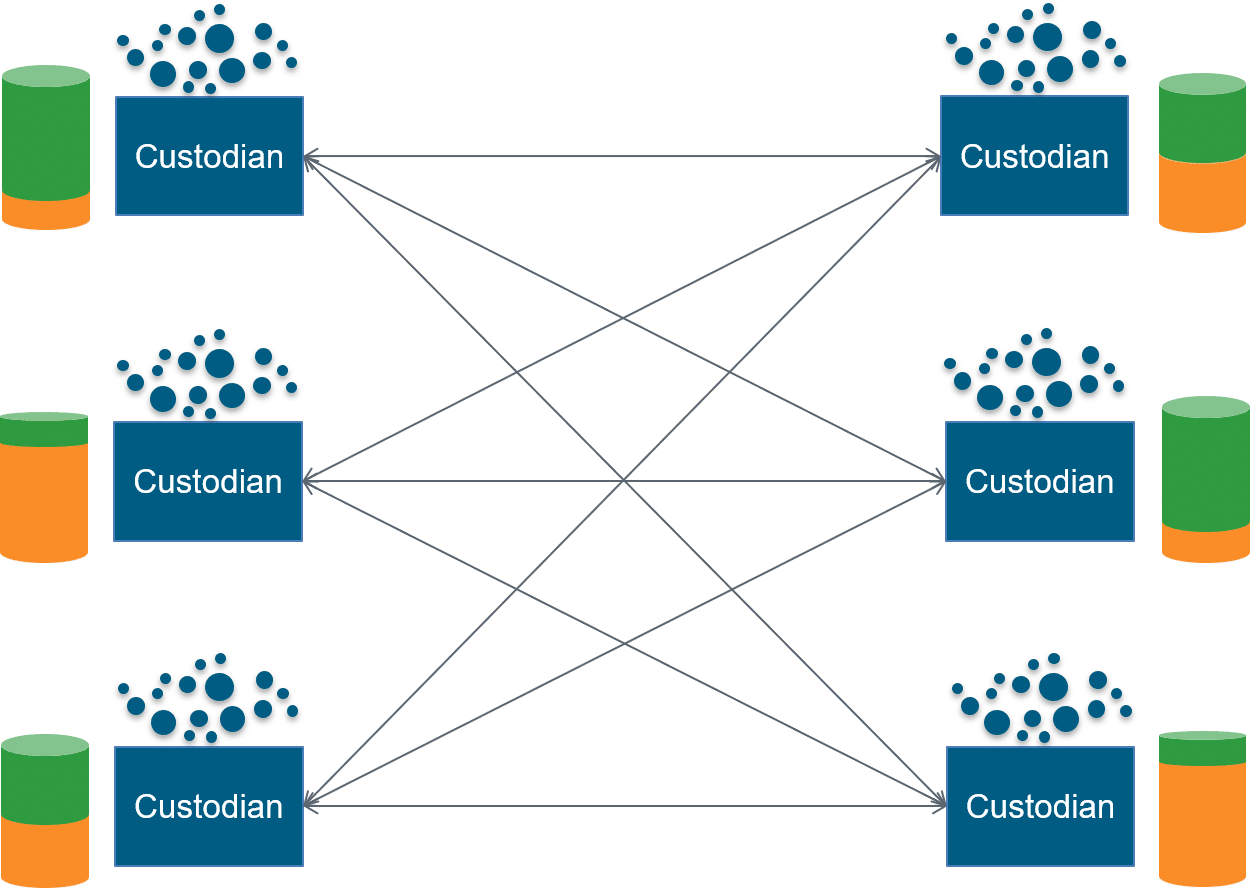

First, there is a chain of custody and payment that can include many types of institution – paying agents, withholding agents, CSDs, global custodians, custodians and brokers to name a few. This vertical can be replicated across multiple markets leading to a network effect. In this network, the interests of the beneficial owner are traced up the chain while the payment makes its way down the chain. Each counterparty in this chain must play a role, but each is limited in what it offers to the other, what it can or is prepared to do and, importantly, what kind of accounts it offers. Most frequently counterparties will use omnibus accounts that aggregate the assets of many clients. This issue, called the Network Effect, occurs at each point where counterparties are involved and it is this that most frequently stops the tax process in its tracks.

Figure 2 The Network Effect

It progressively degrades the ability of a beneficial owner at one end of the chain, through no fault of their own, to obtain their entitled tax rate whether by relief at source or by standard refund. Figure 2 shows how this works (or doesn’t). Each custodian has:

- a counterparty network that provides access for its customers to other markets; and

- its own client base made up of varying types and residencies of client.

Each offers to the others a varying level of tax service depending on the complexity of its own market compared to others. The result is that, even where tax relief is possible, these structural attributes actively degrade the availability of that relief.

The Network Effect is also exacerbated, ironically, by the industry’s apparent addiction to bundled custody fees. Tax processing is hard. It’s complicated, but it’s also high value. However, most custodians in a network offer their counterparty fees and custody fees to beneficial owners on an averaged out, bundled basis. That averaging acts as a brake on investment in technologies and high value processes, like tax processing, that would otherwise improve service delivery. Downward pressure on those fees from investors is equally short sighted because it’s based on a flawed argument – that scalability and technology drive down transactional costs and therefore should drive down fees. What actually happens is that you get what you pay for, and tax is a (high value) product, not a task.

Finally, you had to contend with the lack of awareness of these issues at the beneficial ownership level, a lack of understanding of the processing cost in this environment, and the frustration of knowing that having an entitlement does not always result in getting that entitlement.

So, it doesn’t really matter where you look historically, or which angle or perspective you choose to look at it from – it was a mess and unsurprising that the amount of over-withheld tax that is ever recovered back to the investors is less than ten percent. Things had to change.

The Times They Are a Changing

More recently, in Europe, the findings of the Giovannini Group, the FISCO Group and the Tax Barriers Business Advisory Group together with the OECD TRACE Group all consistently came to the same conclusions between 2001 and 2013. Those findings clearly pointed the way to a model in which the tax authorities disintermediated themselves from direct contact with beneficial owners (claimants). The principle underpinning this is the idea of contracting directly with financial institutions (Authorised or Qualified Intermediaries) to apply the rules on their behalf – under strict liability – and apply tax relief at source as the de facto base model. This idea opens the way for the trend towards changing from a standard refund model to relief at source as the expected primary model.

Information Reporting

Of course, outsourcing such a responsibility adds a new driver for governments and tax authorities. If you outsource the tax relief mechanism, how do you know that your contracting party is doing what they are supposed to be doing? How do you know that the Authorised Intermediaries (AI)/Qualified Intermediaries (QI) has the evidence of entitlement?

This leads to another change in the global model – the introduction of regulatory reporting. In the old standard refund model, the process of claiming from a tax authority was isolated i.e. there is a claim, the claim is evidenced and the claim is either accepted or rejected. The financial institutions played no part other than to certify that they had paid their client. In the new model, as exemplified by the qualified intermediary systems in the USA, Ireland and Japan, the basic principle supporting a tax relief model over a standard refund model, is the possession of evidence of entitlement by the financial institution instead of the tax authority on the one hand, and the requirement for the financial institution to report to the tax authority under the terms of either regulation, contract or both on the other. This contractual model was also enhanced with concepts of further disintermediating the tax authorities by means of accepting electronic self-certifications of residency as opposed to the old method of obtaining physical certificates from tax authorities.

So, even for an evolutionary landscape, it’s clear that people were thinking about improvements. Unfortunately, three years on and we are still only seeing fragmented attempts to adopt these models based on the core principle of correct taxation of cross border income under bilateral treaties. So, something is missing. Something different has to come into play to take the obvious benefits of a different approach, and make them real. Enter now, a geo-political factor that would prove to be pivotal – tax evasion.

The US’ QI model was supposed to achieve two things – provide a model for tax relief at source and ensure US income paid to US account holders was reported to the IRS by QIs. A lack of take up of the QI program was partly responsible for the ultimate development of FATCA. FATCA in turn was the progenitor of the AEoI and CRS frameworks. (CRS being the rules under which financial institutions gather and report the assets of foreign resident account holders to their domestic tax authorities. AEoI being the mechanism under which those various governments share those CRS obtained data with each other.) The common factor is reporting. The QI/AI model for taxation of income assumes a reporting obligation for the purpose of making sure tax relief is correctly granted by a financial institution. The FATCA/AEoI model also has reporting, but for the purpose of identifying potential tax evasion. However, much more effort and attention has been given to anti-tax evasion efforts recently and thus, ironically, it’s anti-tax evasion that has triggered renewed interest by governments in getting systems in place, a side effect of which is that technology and digitisation are being recognised as necessary for this change.

Paradigm Shift – the Name of the Game

So, now let’s look to the future and to that paradigm shift. Everything we’ve described so far would probably be described as an evolutionary change. So, what would take us from evolution to paradigm shift?

Technology

It’s clear that new technology is available – artificial intelligence and machine learning, distributed ledger technology, API connectivity, the rise of ‘platform processing’ – all represent the opportunity for a major, almost seismic structural change in the way we do things. This could be as big for the securities industry as the iPhone was for Apple. In particular, platform processing provides a secure digital environment that allows for standardised functionality, digitisation, transparency embedded in an opaque environment and common access for intermediaries to the most efficient and integrated processing.

One could argue that a paradigm shift should be a full blockchain or AI development of tax processing. Unfortunately, if that were true, we would be assuming that our rate of change would be similar to technological change rates – which just isn’t true (see Figure 1), and that all the factors affecting adoptability (need, desire and belief) would overcome multiple and cross connected supply chains. No, what we’re talking about here is platform processing.

Converting Specialist Knowledge into Added Value

Platform technologies allow for that paradigm shift, in context to our industry. Most financial institutions are now comfortable with the idea of ‘added value’ processes. While they remain extremely uncomfortable with any technology that could disrupt them out of business and make their existence irrelevant, they are now comfortable with outsourcing processes to specialists. Pressure from regulators and clients and counterparties is making them more comfortable with alternative solutions that reduce their cost and/or risk and leverage technology. They are more comfortable with the ideas of unbundling fees to express more clearly where they add value to their clients. These technologies also allow for the complexity of manual systems to be adopted, adapted and eventually automated behind the platform and not in front of it.

At the same time, while we’ve waited many years, the work of the various groups to establish an effective operating model can be shown to have solidified into a set of workable principles all of which can be built into a platform. What’s needed is actually a hybrid blend of fintech and tax expertise.

Fin-Tax – Is It A Thing?

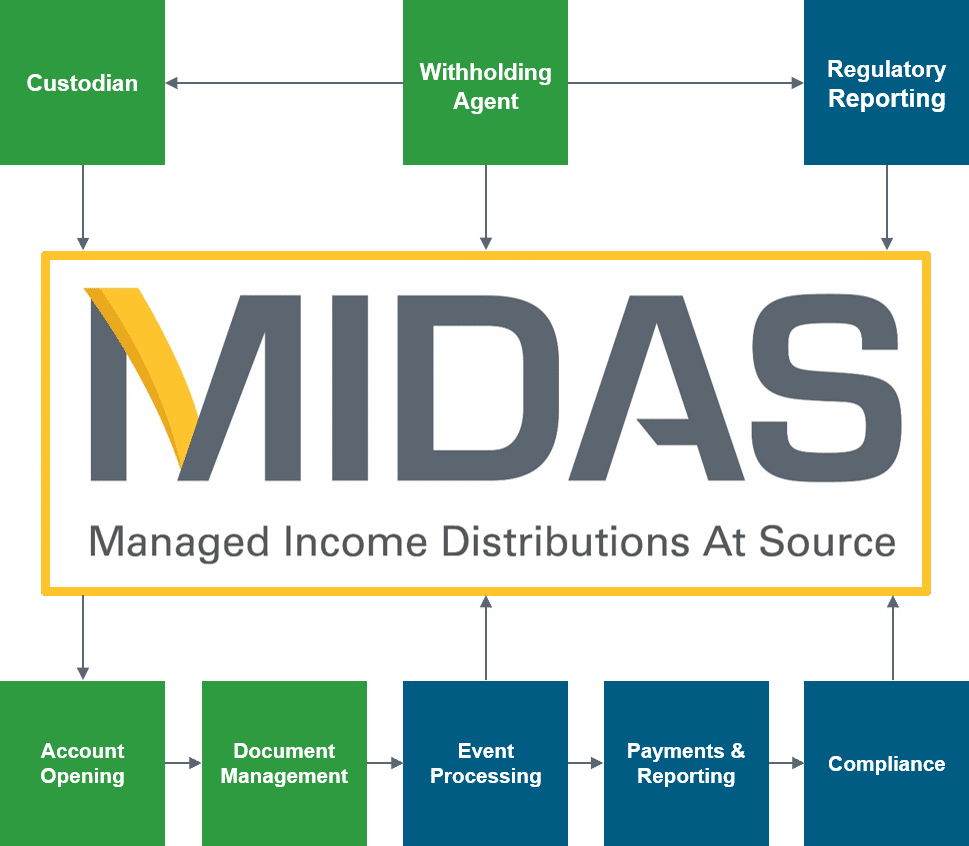

Let’s take a look at what that ideal platform would look like (see Figure 3). The driver behind such a platform would be the joint efforts of governments to combat tax evasion and have an efficient mechanism to apply tax relief at source with standard refunds being a backstop. This reduces workload on the tax authorities and has the financial community picking up most of the workload. The framework would ultimately be an AI (or QI) model with a governance control and oversight mechanism including annual reporting (whether for anti-tax evasion or for income processing). The benefit of a platform here is that most financial institutions struggle with the sheer number of governmental, as well as financial, counterparties that would need to have information delivered to them. A platform approach allows for this information to be accessed rather than delivered, thereby increasing data security – a matter that has been excluded from this discussion, but is by no means irrelevant.

Figure 3 Platform based processing for cross border tax networks

But a platform needs a combination of data and documentation to perform its primary role. The digitisation of documentation is well advanced in other areas of finance but has lacked penetration in the tax space for all the reasons already described. Certificates of residency are progressively being replaced with self-certifications and these in turn are being increasingly permitted in digital form along with digital signatures.

The Omnibus Conundrum

The other main obstacle is the use of omnibus accounts. For a tax relief platform to work, the financial institutions, at all points in the custody chain, must be able to continue to operate these accounts, in order to benefit from their efficiencies, while the platform provides the environment in which the assets within them can be allocated to documented beneficial owners. Reliance on local KYC and AML rules as the base for the AI/QI contract ensures that, while claims are supported by self-certification, these are backed up by robust regulatory compliance obligations within each firm.

Figure 3 shows how these functions can be embedded into a single platform. In a counterparty custodial-withholding network, most custodians will operate a combination of omnibus, rate pool or client segregated accounts. Tax relief will only be granted by a withholding agent (AI) if they have the transparency to all the underlying beneficial owner’s documentation and allocations in order to mitigate their strict liability to the domestic tax authority.

For the withholding agent, this is a nightmare network because they may be operating with upwards of twenty counterparties for any given corporate actions event. For the custodians, solicitation and validation of tax documentation is difficult at best, finding a centralised resource to the various rules, time deadlines and procedures for the delivery of such information to a withholding agent is costly, complex and manual. The platform approach allows both parties to access a single resource to allow solicitation and validation of the documentation, delivery and matching of record date positions at omnibus level, while also matching the aggregation of underlying positions to the omnibus level. All without disturbing the existing counterparty account structure.

The Tax Authority Toolkit

Tax authorities understand that automation is the only way to go, but they lack funding and human resources in many cases. Outsourcing of the withholding obligation will be the first step and has already occurred in several markets; that trend is increasing. This means that there will be increasing attention paid to control and oversight through reporting. This too is currently fragmented, but, in a platform environment, not only is all the data naturally reconciled and present in one place, it also does not need to be transported anywhere – it can be accessed under suitable security conditions. Tax authorities permitting self-certifications of residency also decreases their workload, and allowing digitisation helps the industry to solicit and validate these quickly and in high volumes. A platform also provides a central repository where, should a tax authority wish to audit a claim, it can see financial data on the one hand and the self-certification of residency on the other.

Of course, human beings still exist in this environment and, it’s with their taste for delay that legal structures vary by market providing ‘windows’ of opportunity limited by statutes of limitation for submitting claims. In other words, if documentation is required prior to pay-date for tax relief, there are quick refund and standard refund processes that are still available if a beneficial owner or financial institution fails to make a deadline. The platform approach provides a rare opportunity to assimilate and automate these processes which are usually handled separately and manually by most firms.

Windows of Opportunity

One more thing that this platform-based approach brings is the opportunity for integration. There are typically three windows of opportunity – relief at source (on pay date), quick refund (usually 30-60 days after pay date) and standard refund (anything from pay date +1 to pay date + twenty years). Which window(s) are available to any financial institution or their customers is usually dependent on when the supporting documentation is available to the withholding agent. In a platform model, unlike the models operated by individual bilateral pairs of financial institution, any portion of a record date position of any given beneficial owner that is not elected in one window (due to lack of documentation) can automatically be moved into the next window without human intervention. Once the documentation is made available, the process available at that time can be implemented without further delays.

The Paradigm Shift

So, a platform approach provides a framework within which all the various initiatives can come together:

- self-certifications with digital signatures making life easier for beneficial owners

- transparency within omnibus structures allowing financial counterparties to operate omnibus accounts while providing breakdowns of those accounts to the platform for tax relief processing

- Data governance through platform validation and matching of inbound position data from counterparties to reduce risk and limit liability

- Control and oversight through access by tax authorities to the platform data, removing the need for sensitive data transfer and paper-based claims by beneficial owners and further reducing the workload on tax authorities.

Without a platform, it’s unlikely that any individual automation or standardisation initiative will have enough effect to create momentum for substantial change. What’s needed is a vehicle for those changes to plug in to. That’s the name of the game.

Conclusions

Where we started was a world in which the basic withholding tax model was a standard post pay-date reclaim with minimal chance for relief at source. A world where claims had to meet strict and constantly changing evidentiary rules established more by reactionary forces than by intelligent pre-planning. A world where certificates of residency are issued on paper by tax authorities, where tax vouchers are issued on paper, where tax claim forms are paper. A world where omnibus structures would require chains of paper-based tax vouchers to evidence the trail of beneficial ownership. A world where complex investor structures usually got no claims processed because it was too costly or too complicated for them and for their financial institution. A world where the receiving tax authority had little or no technology, had enormous backlogs of claims due to insufficient human resources and generally created a fragmented payment landscape in which claims might get paid in weeks or decades depending on the market concerned.

In the five decades between 1963 and 2013, the tax landscape managed to get from a model tax convention all the way to some basic ideas about how we might improve that landscape without really changing anything much of substance. In the same period, the technology world managed to put a man on the moon, go from spreadsheets to the world-wide web, invent personal computers, text messaging, AI and distributed ledgers. Even ABBA manged to get from a small Swedish group no-one had ever heard of in 1974, through a musical, two movies, 500 million in record sales, to being holograms you can actually perform with in 2019.

In 1992, Martin Foont founded a small company in New York called Globe Tax Services with just two people. Within ten years, all four US depositary banks were using GlobeTax to provide tax relief and claims processing on American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) and many US Prime Brokers used the company because no-one else could do what they did. Within the next five years the company had the largest market share in processing tax claims directly for US institutional investors and a growing international client base. Most of this business was in standard refunds that were gaining in complexity and cost to process. In 2009, the company launched ESP, its first electronic submission platform allowing DTC Participants to elect for tax relief on ADRs. By 2016, GlobeTax was processing two million claims for relief and standard refund and by 2018 that had risen to more than seven million. 2018 also saw the early adopter phase of the firm’s second and this time, global platform – MIDAS (Managed Income Distributions at Source) which is due for its full roll-out in 2019.

Participants in that platform can continue to run their businesses as they want. But from a tax perspective, the data they send and documents they upload, allow them to apply tax relief on cross border investment income in an integrated way across multiple jurisdictions, with full transparency to counterparties within omnibus accounts and capacity to include complex transparent investment vehicles as well as simple beneficial owners to their service offerings. Embedded Apps such as eCerts and eDocs allow for solicitation and validation of self-certifications within the platform and submission on non-certification tax documentation such as powers of attorney and letters of authority. The platform approach also allows for newer technologies to be incorporated easily such as XBRL tagging of market handbooks, electronic signature and, eventually, distributed ledger technology and AI.

So while the payments industry is working on blockchain, AI and robotics, the back office corporate actions and tax services space, is just now facing the need to implement platforming as an enabling technology. This is the standardisation and automation which will ultimately be the pre-requisite precursors for the disruptive technologies used elsewhere. In that context, platforming is both necessary and will be a true paradigm shift.